Horrible Art: Volume Three

- Jan 13, 2021

- 9 min read

I've taken an exceptionally long break from writing recently! Over Christmas, my shop went a bit mad with orders and I found it difficult to manage all of my projects so focused on the one that was offering monetary gain, obviously! And I was busy focusing on the joyous celebration of Sol Invictus. But, I'm going to try to get back to regular writing and scrutinising and poorly researching.

And so, back to art again! I had never realised how much I missed art theory and the act of reading a painting until I started really putting it together with my love of horror. Art is something I've always enjoyed. It's always been a great way to express myself, whether through my creations or simply by letting people know which artists I love, which movements I relate to, and what kind of art I hate. I remember once being asked by family friends who my favourite artist was when I was around seven or eight. I said Van Gogh. They laughed at me because they meant artist as in my favourite band. Then they patronised me and said it was great that I had a favourite artist. They also, on the same night, laughed at my Monster's Inc Slime Playset sculpture, but in all fairness, it was really phallic. And I did realise that when I went back through to the kitchen sadly with my work of art and then giggled to myself about it.

But anyway!

More horrible art, and not necessarily of the phallic variety. Every time I do a bit of research for a post on horrifying or spooky art I find more pieces that I've either never heard of or had completely forgotten about, and so it's a never-ending cycle of me writing about art, researching art, discovering art.

To start off this collection, a true classic. Can anyone really deny the horror clearly portrayed in Hieronymous Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights? The triptych's portrayal of creation, human nature and behaviour, and the demise of man is a beauty to behold. And we don't really know what Bosch was trying to say to us. For me, the three panels, starting from left to right, show the Earth's unfortunate descent into Hell, or Earth becoming Hell. We have the virtuous, biblical Garden of Eden on the left panel. The world before scene. On the center panel, we have carnal desire, expressions of love. Still peaceful and beautiful. And in the third, a Hellscape of darkest nightmares. Horrifying beasts, methods of torture, humans suffering. It's deliciously creepy, and you can get a better look at it on the Museo del Prado site, or check out this interactive version which includes helpful markers and exceptionally high quality zooming capability!

We don't know a lot about Bosch, but he has other works which echo the themes of The Garden. It seems to be a predisposition towards drawing the human specie's slow demise and the punishments we will receive for our actions. Both The Last Judgement and The Haywain Triptych feature the same theme of Hell as the final stage, whether in individual life or humanity's greater final destination. Basically, we're doomed.

I love the detail in The Garden. It seems like every time I look at it, I find a new favourite image, a new death or torture I hadn't previously noticed. There's something extremely morbid about it, like I'm looking into my own future. Because, if Hell existed, that's most likely where I'd be going. So am I preparing myself, or torturing myself? Who knows.

Now bear with me, because I'm about to go deep. Because our next painting stands for America's past and how their sensibilities loom over their present so heavily that it's impossible for them to change their view. And this pride in their puritanical, pilgrim praising past is no better exemplified than in one of the great works of Americana.

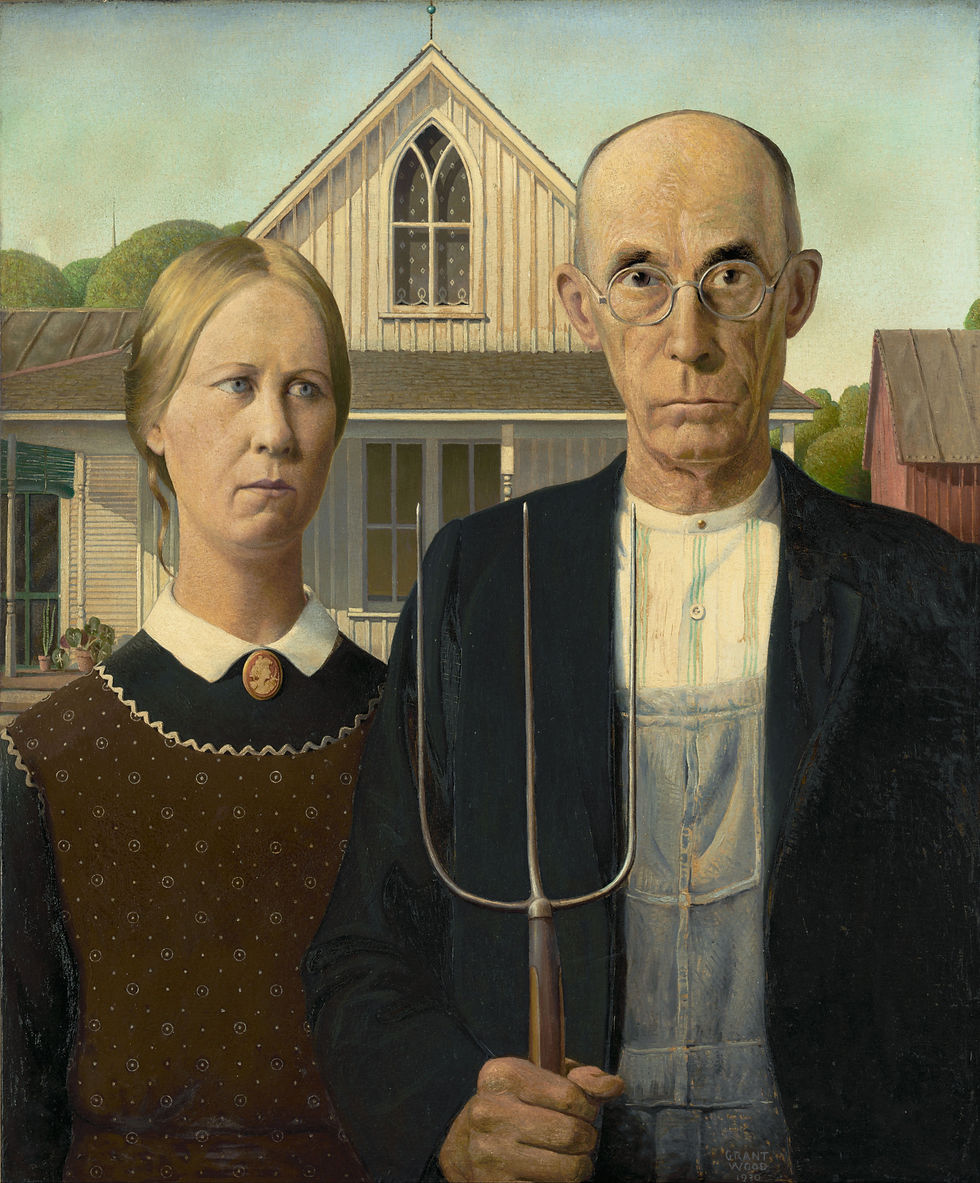

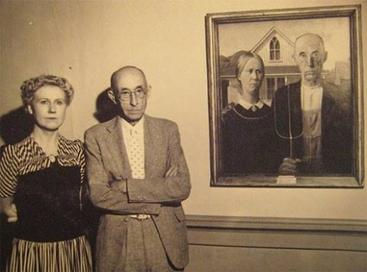

Grant Wood's American Gothic is a painting which may not necessarily strike fear initially, or at all, but is nonetheless horrifying in what it represents. Completed in 1930, the tremendously famous portrait shows a farmer and his daughter (often mistaken for his wife) posing in front of their American Gothic farmhouse, the architectural style giving it's name to the painting. There is a deep nostalgia in the painting for a time period only barely out of reach of the 1930s, and this nostalgia is misplaced and represents a scourge on America and her people, specifically those indigenous to the continent and those forcibly brought here.

American Gothic features two people, a pitchfork, and a house. And all of these elements signify a specific aspect of traditional American life, as well as echoing contemporary American society. To begin with, the pitchfork. A symbol of farming, a tool used in horror so well as a weapon, a trident to bring forth an image of old Gods. The pitchfork is mirrored in the stitching of the farmer's overalls, along with the sectioning of his face. Bringing forth imagery of the protestant work ethic of the pioneers, the pitchfork symbolises America's industrious, hardworking past. And not to take away from the work ethics of those who farmed the lands and worked their way West, they were following their Manifest Destiny, but were they really the embodiment of hard work?

Given that shortly after the arrival of white Europeans in America, more than half a million Africans were brutally and traumatically captured and forcibly brought over to do the hard work, is the white, Protestant work ethic really something that should be given focus in the view of Americana? This hypocrisy is challenged by Gordon Parks' photograph, American Gothic, from 1942, showing Ella Watson, a black worker and mother, doing the work of both the characters from the original painting. A symbol of the American societal systems and structures that are conveniently left out of the apple pie peacefulness of traditional Americana. And yet, this seems far more American in nature. The flag, the stoic face of hard work, the holder of multiple jobs in order to make ends meet. A black face. A woman's face. The truth of America.

Now to the two figures in the painting. These were modelled by Wood's sister, Nan Wood Graham, and their dentist, Dr. Byron McKeeby. These figures have been speculated to be representations of Wood's mother and deceased father. And people have a bit of a field day reading into Wood's supposed Oedipus complex. And though I personally like the idea of them representing Gods of the underworld, I think they represent traditional American values and, ultimately, the life and death of America.

Their clothes, plain, simple, old fashioned. The hairstyle of the daughter, sensible and modest. Their faces, void of any semblance of unnecessary emotion, evocative of traditional photography of the time. They are quintessential Americans, supposedly. The Americans that America want to be represented by. Hard working, descendants of the pioneers. Working their share of the land and surviving with no help from others. The American dream: self-made men with their share and the ability to make their own wealth. What's more American, and more horrifying, than the white man, head of the household. His work is his own, his land is his own, and his daughter (and any other women for that matter) his own.

And finally, the house. Based on the Dibble House, the Carpenter Gothic style home is representative of America at it's core. Bright white panelling, simple and modest yet effectual styling. Maintaining the roots of colonial farming yet adding a semblance of home pride with delicate, pretty features. It's one picket fence away from being the true representation of the Hellscape that is suburbia. And this house holds the key to the horrifying truth of America. A country, unable to let go of it's past. Disregarding a majority of it's history and actions in favour of the more glamorous and story-worthy elements of it's creation. A people, far too unable to admit to the fault of their ancestors to stop celebrating genocide and destruction. Standing, stoic faced, holding on to the past. That's the horror behind American Gothic.

But less depressingly! Next up is a painting which just embodies absolute Goth aesthetic. The high-pitched guitar solo of the art world. A perfect avatar for any emos that are still lingering in today's world.

Vincent van Gogh is typically a painter of beauty, whether in the ordinary, such as Sunflowers, or in the whimsical and mystical, such as The Starry Night. But behind his façade of colour and beauty, it's well-known that his is a story of tragedy and mystery. His bright colours give way to a man unappreciated in his time, never knowing his worth and his talents. And in line with this emotionally dark theme, I bring you one of his most surprising works.

Head (or Skull) of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette was most likely a joke, painted by Van Gogh in an attempt to mock the laborious and repetitive task of painting skeletons, a common practice in art schools at the time. As opposed to developing the anatomy and composure of death and the body, this skeleton looks cool as fuck. Not that smoking is cool. But it does look kind of cool.

And while the painting contains classically spooky, and pretty fucking metal, imagery, that's not the real source of it's horror. To me, horror lies at the door of the joke. That Van Gogh's humour and satirical efforts were overlooked and underrepresented. Where we see him now as a struggling artist, unappreciated in his time, but known for true beauty, we could be seeing him as one of us. A normal person, who made dumb jokes and dedicated themselves to the thing they loved despite a perceived lack of appreciation. There's something deeply humanising about comedy and being stupid, and the horror is that this often escapes others and ourselves, especially as we battle inner demons. It's difficult to articulate what I'm trying to say, and so I hope I captured it here. I think it's the same kind of sadness and fear that comes from asking people to laugh at your funeral or your wake. You want to be remembered in laughter and humour. You're desperate for it.

I keep saying that it gets less depressing, but so far I've lied. Just assume from here on out that it's going to be kind of mood-bashing. And if you're not into that, just look at the pretty pictures and ignore the paragraphs.

I couldn't find a lot of deep information on Aksel Waldemar Johannessen (the translation on this Wikipedia page is adequate but brief) and so I was left a bit lacking. But what I did manage to glean is that he follows in the steps of Van Gogh somewhat. His paintings were only exhibited after he had died, and so he never got to experience his work being celebrated and enjoyed. (I would be so grateful for any free, online resources on Johannessen to bolster this information at a later date so if you know of anything, please provide!)

Johannessen's painting, Die Nacht (or The Night) is similarly shrouded in mystery across the internet. I even ventured onto page two of the search results to see if I could find any further discussions or information about the work, but to no avail. But that just makes it extra spooky! It's open to interpretation more so than any other painting I've covered, and boy can I interpret things in a spooky way.

There's a bit more information on Johannessen's sad, short life at this page, where details of the sad events he endured offer an explanation to the dark, dull and cold colours he frequently utilises in his works, along with the often melancholic themes. It's key to note that a lot of his figures tend to be shown as sort of ethereal, almost as though they are partly human and partly of spirit. This definitely seems the case in the figure from Die Nacht.

The slight glow protruding through the night, yet the sheer evidence and solidity of the figure suggests a state in limbo. Part of both worlds, not dead nor alive. It floats directly in the field of vision of the viewer. I imagine waking up at night, roused from sleep for an undeterminable reason. A primal instinct whose only recognisable remnant is a shiver across your back. Drawn to the window, you look out on a figure. Glowing, but not radiant. Seemingly hovering above the ground. A warning? A sign? A pleasant omen? Who knows. But it was destined that you wake up and see it.

But there's something so...normal about it? Something mundane in quality. Like a lot of Johannessen's art there seems to be a sense of everyday expectancy in the sadness. As though it is inherently a part of our lives so much we might not even recognise it straight away. That loneliness, the weird, the uncomfortable, the hardships, the cold night, are so intrinsic to our human being that they're almost boring. Completely expected.

And I always expect to see a haunting figure shrouded in sadness when I look out of my window at night. Doesn't everyone...?

Comments